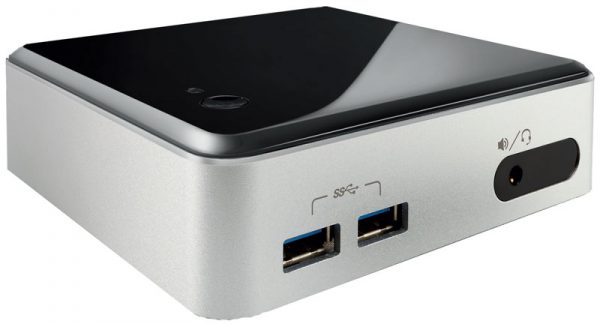

Tiny PCs like the Intel NUC are limited as replacements for the desktop, but they’ve come into their own in harnessing the media-decoding prowess of new chipsets to drive an HTPC. Coupled with free media centre software, it’s become possible to put together a powerful little set-top box that can compete with the behemoths of only a few years ago.

Tiny PCs like the Intel NUC are limited as replacements for the desktop, but they’ve come into their own in harnessing the media-decoding prowess of new chipsets to drive an HTPC. Coupled with free media centre software, it’s become possible to put together a powerful little set-top box that can compete with the behemoths of only a few years ago.

It’s actually feasible to do it even cheaper than that if you use a Raspberry Pi flavour of your chosen software, or even adapt an older PC that’s set for retirement, but my desired integration with my existing setup and a handful of esoteric requirements made this an appealing route.

- Lossless HD audio over HDMI was a must, and many motherboards are finicky about this

- Built-in wi-fi, SD card reader and IR saves a lot of messing with peripherals and USB hubs

- I aim to rip Blu-rays to this thing without recompression, and I don’t fancy a £30 computer to handle those

The hardware

I spent £170 on a Zotac Zbox Nano AQ01, which nets you the box without RAM or internal storage. I recycled a 2GB RAM stick from when I upgraded my laptop – somewhat anaemic, but fine if media playback is all you’re planning – and dug out the old 60GB HDD that used to inhabit my PS3, which is more than capacious enough for the OS if you’re using external media storage. The box has seven USB ports (2x USB 3.0 and 5x 2.0), so you have plenty of scope to add capacity later.

If you don’t have the skeletons of various computers around to raid, you could plump for the more expensive Plus model, which includes 4GB RAM and a 500GB HDD. An even cheaper storage option if you’re relying on external or network storage and want a pure XBMC machine is a low-profile USB flash drive like a SanDisk Cruzer Fit, which can slot into the back and never have to be seen again. You’ll want at least 8GB as even though XBMC isn’t very large, the library of high-quality artwork it caches for your movies can be.

The Zbox AQ01 runs on AMD’s A4-5000 platform. That’s based on the same Jaguar architecture found inside the PS4 and Xbox One and has GPU-accelerated video decoding, ensuring smooth playback of high-quality video. It’s more than capable of general computing tasks if you install a full OS like Windows or Linux on it, but I’m not interested in that.

It has HDMI (also DisplayPort), optical audio, Wi-Fi (802.11ac), Bluetooth, gigabit Ethernet, a 7-in-1 memory card reader and, pleasingly, a built-in IR receiver. In short, it’s incredibly well-equipped considering the compromises I was looking at making in building my own, much physically bigger and more expensive, HTPC.

The software

For this project I’m sticking with what I know, which is XBMC. I first used it circa 2004 when it was Xbox Media Center, a staple of the modded Xbox scene, and since then it’s expanded to other platforms. I’ve opted for its OpenELEC form, a stripped down version of Linux bearing only what it needs to run XBMC. It’s fast, light on resources, and takes up very little space. A similar option is XBMCbuntu, which leans slightly more towards flexibility at the expense of hardware requirements.

XBMC also runs atop Windows and the Zbox will happily run it, but a licence costs almost half as much as the machine, so forget that.

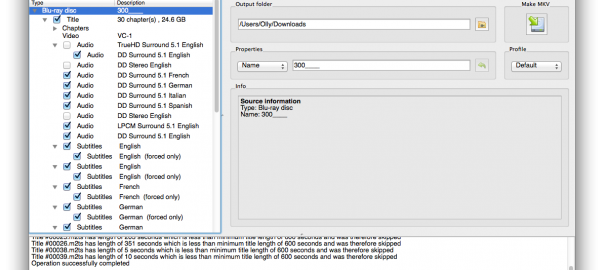

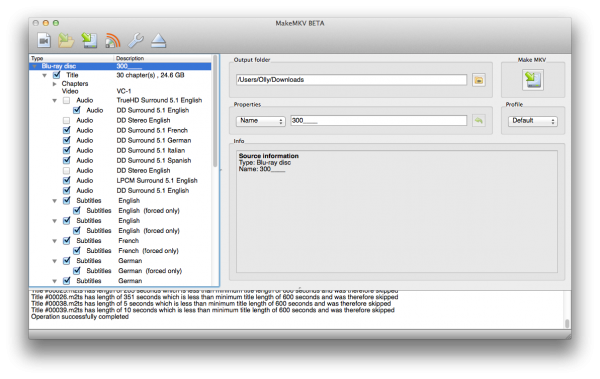

The process of ripping DVDs and Blu-rays is handled on my main computer, using MakeMKV to generate a lossless rip and HandBrake to compress the DVDs. Using this, I can get a DVD movie into around 1.5GB with little quality loss. BDs are staying in all their 30GB+ glory, HD audio and all. I started with a 1TB USB drive that didn’t last me through a tenth of my collection before I had to move to bigger, more expensive network storage (a Synology DS214se with 2x 4TB HDDs), but it should suit most users.

Installation

With the Zbox all working and the OpenELEC installer on a flash drive, all that needs doing is popping that into a USB slot, turning it on, and running through the five-minute installation. I couldn’t get the Mac script to correctly create a bootable USB drive, but I ran the Windows version instead without issue. That’s really all there was to the setup, as things are basically ready to go from the start; run through the settings to get things configured how you want them, point XBMC at where your movies and TV shows are stored, and you’re off.

Skins and add-ons

I’ve frequently found that UI design isn’t a strong point of open source software, and the majority of XBMC skins I tried did indeed look like they were designed by teenage boys. The default skin, Confluence, is a solid choice, though. My only major complaint was that it lacked a library view that fulfilled my dual aims of putting the lovely artwork and metadata to good use and being usable with my large library. The ‘fanart’ view wastes a lot of space.

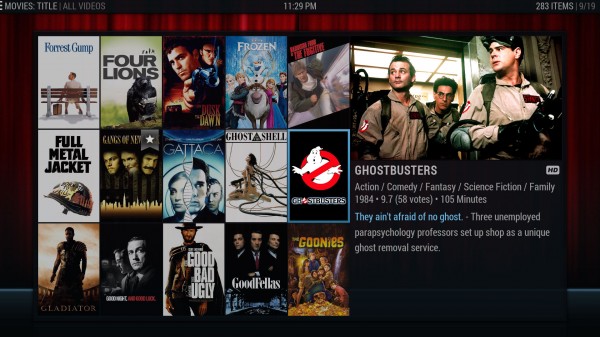

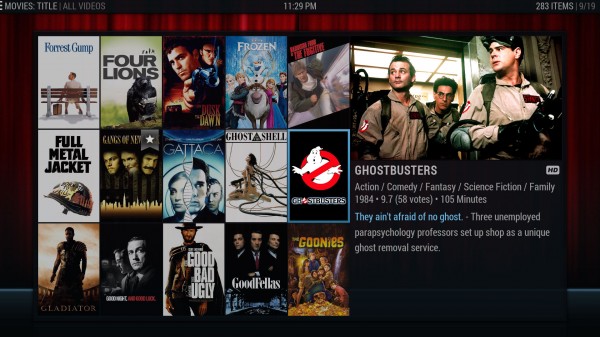

I eventually settled on Aeon Nox. The more granular control over the main menu is nice, allowing me to drop options like sets, which I’m never likely to use, and create my own shortcuts to unwatched movies and similar filtered lists. A classy set of background images reins in the main menu − that open source design again − and the ‘infoview’ option allows me to see more movies at once without sacrificing the poster art and metadata:

An honourable mention goes to Quartz, which convincingly imitates the Apple TV interface. Very slick and would have been a contender for my skin of choice were it not for the lack of anything as good as the above view.

Issues

A niggle more than anything would be that programming my Harmony remote to perform anything but the most basic functions – anything not on a generic Windows Media Center remote – is a world of XML files and key listings that I frankly can’t be bothered to get into. I also can’t turn on the Zbox with the remote, though I sense that’s going to be a common limitation unless I fancy leaving the thing in hibernation 24/7. Shutting down that way works fine.

I’d also suggest Intel or Nvidia graphics hardware if bitstreaming HD audio is your intention. AMD’s Linux drivers are a bit naff, and although it’s not impossible to get it working, it’s a daunting process. For now I’m letting XBMC handle TrueHD and converting DTS-HD to FLAC during the ripping process. If a future OpenELEC update enables proper HD audio support, brilliant; if not, no big deal.

Should you be less finicky about such things, though, you’ll have no problems with this setup. It’s going to take me a good while to get everything ripped – 284 down, approximately 500 to go at the time of writing, not counting TV shows – but when it’s done I look forward to reclaiming some shelf space and having an on-demand box that, unlike Netflix and friends, actually has a library I’m interested in.

The first is a simple lack of horsepower.

The first is a simple lack of horsepower.  First task, of course, was wiping out Windows 10, saving the key for future use. Massive overkill and much more effort to maintain than a purpose-built media centre OS. My software of choice, XBMC, is now Kodi, and OpenELEC has been supplanted by its better-supported fork,

First task, of course, was wiping out Windows 10, saving the key for future use. Massive overkill and much more effort to maintain than a purpose-built media centre OS. My software of choice, XBMC, is now Kodi, and OpenELEC has been supplanted by its better-supported fork,  Tiny PCs like the

Tiny PCs like the